In 1987, a young lawyer fresh from national youth service, was nursing the idea of an organization to address widespread abuse of human rights in Nigeria, then under military rule.

The young lawyer, Clement Nwankwo, bounced the idea off an older professional colleague, Olisa Agbakoba, and he welcomed it warmly. Thus, was born the Civil Liberties Organization (CLO) – Nigeria’s first formal human rights organization.

It was the first non-governmental body in Nigeria dedicated to the defence of citizens against human rights abuses. These are the fundamental rights now enshrined in Chapter Four of the Constitution, covering the right to life, the right to dignity and freedom from torture, freedom of association and freedom of expression, among other rights. CLO’s emergence was also the precursor to others such as the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights, Human Rights Africa, Constitutional Rights Project, and the Campaign for Democracy.

Under prolonged, and often brutal, military rule in Nigeria in the 1980s and 1990s, these rights groups, along with trade unions and students, became the only voice of opposition to the military’s authoritarian excesses.

For Nwankwo, now 59, it all started with his stint during National Youth Service in the Legal Aid Council in Ijebu Ode, Ogun state in 1985-86. His brief included prison visits, during which he came across many cases of people held without trial for years while the wheel of justice stalled. Many of the cases were about long-distance bus drivers charged with manslaughter after they were involved in road accidents between Ore and Shagamu on the Lagos-Benin expressway.

After he successfully defended one of the cases, secured a driver’s freedom and survived a violent mob angry at the verdict, Nwankwo began to get a flood of requests. Dealing with such cases now became the mainstay of his practice after his national service and return to his Lagos base.

Nwankwo was introduced to Olisa Agbakoba by a common friend. Agbakoba subsequently provided him office accommodation in his maritime law practice.

“One day I walked into Olisa’s office and told him I was thinking of setting up an organization devoted to dealing with these kinds of cases,” Nwankwo recalled in an interview with this magazine.

According to Nwankwo: “He welcomed the idea but said he didn’t have enough time, if I would be ready to do all the running around? I said yes. Then we began to think about a name. Suddenly Olisa’s eyes caught a book on his shelf titled ‘Civil Liberties’ and said, why don’t we call it Civil Liberties Organization? And that was it. CLO was born.”

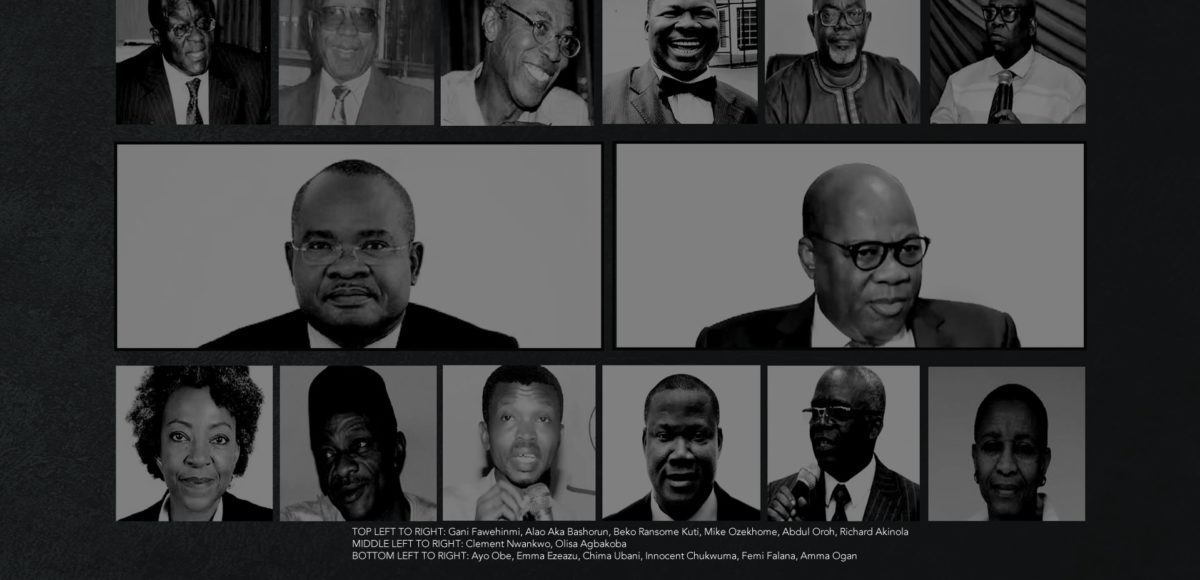

Agbakoba became the first President of CLO, with Nwankwo as the National Secretary. Other members such as Abdul Oroh, Richard Akinnola, Emmanuel Erakpotobor and Mike Ozekhome joined afterward, and membership grew rapidly. The early work was focused on police abuses and awaiting trial cases in the prisons. Its impact was immediate as it led to freedom for scores of wrongfully imprisoned people.

When CLO published its first annual report on human rights in Nigeria, in a widely publicized event that had the Founder of Amnesty International, Peter Benenson in attendance, the police found it so damning, the then Inspector-General of Police Muhammadu Gambo Jimeta ordered the arrest of the principal officers. They were freed without charges after five days. Yet it didn’t deter the organization from pursuing its goals and achieving some spectacular results, such as exposing the existence of the secret island prison – Ita Oko, off the coast of Lagos, set up by Olusegun Obasanjo’s military rule, and causing its closure.

Human rights Activists Beko Ransome-Kuti and Femi Falana were to set up the Lagos chapter of CLO but ended up setting up the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights. Nwankwo subsequently left CLO as well, to found the Constitutional Rights Project (CRP).

After his departure, there was an infusion of activists from the student union movement, drawn mainly from the National Association of Nigerian Students (NANS). These included Emma Ezeazu, a former NANS president who succeeded Nwankwo as national secretary, Chima Ubani, Lanre Ehonwa, Innocent Chukwuma and Ogaga Ifowodo.

Many of these Activists suffered stints in detention or physical attacks for their work. And it was largely due to their campaigns against military rule that democracy, though imperfect, was delivered to Nigeria in 1999. This created a crossroad for many activists, a dilemma some resolved by getting rewarded with political appointments, ostensibly in the hope of changing the system from within.

It was no doubt a defining moment for the human rights segment of Nigerian civil society groups. It is noteworthy that while the early stage of the movement was defined by campaigns that were largely political in nature (protests, denunciation, litigation, etc.), the second phase has seen more specifically targeted interventions, such as those focused on changing policy or legislations, often achieved through engagement and awareness creation than otherwise. The field remains continually evolving and it would be right to expect that more changes and innovative approaches to addressing these and other issues will emerge.